I have a leopard print problem. It started almost a decade ago. Yes, I’d dabbled before. A ballet flat here. A shirt collar there. Even some (deeply regrettable) jeans at one point. But that was just amateur quaffing. In 2017, I left the after–work drinks and went full–time blotto.

I was two years into a research fellowship at Oxford University. Before that, I had undergone close to a decade of training in ‘the arts’ which had proven a complete waste of time and coin. Some monkeys can’t be taught. Now, I had joined the semi–real world of wildlife conservation where I was to bring my arty little perspective and make interdisciplinary magic. I won’t pretend I didn’t have high hopes for this thing. After years of not getting the point of me in academia, but lingering awkwardly on because the alternative ‘real job’ seemed marginally more grim, this was the ticket to acceptance and fulfilment. In a freshly minted research position that did not exist before me, I de facto couldn’t be worse than anyone else. All I wanted, literally all I wanted, was to be the one to solve the extinction crisis and maybe do a bit of voiceover work for a BBC wildlife documentary.

Instead, I floundered in the odd cross–human experiment, with too much self–reckoning and not enough savior–making. I was confronted by the fact that I was, I am, a very unserious person. When co–workers discussed (statistical) modeling, I exposed myself by assuming the sexy fashion people. They talked of R and Python. But these were not movie ratings or medieval snakes. I was an invasive species. I spoke a different language and experienced a different reality. Where were the binoculars? Where were the soothing tones of Attenborough? Where was the wildlife?

After two years all I had published was a piece about dodgy–looking lions with human faces. The pinnacle of my earlier art ‘career’ had been a 17th century writer who measured a painting’s success by the potency of his erection. I was irrelevant. Worse, I was unhelpful. I needed in.

I found myself in a staff meeting opining the dwindling support for lion conservation in Britain (since there are no lions in situ, shouldn’t we be saving the local hedgehogs, etc.). I started thinking about how lions were actually all over the country. Just culturally. The three lions on the national football shirt. The four lions in Trafalgar Square. The lions stamped on the 32 million eggs eaten by Britons every day. What if each time their image was used, just like when a piece of music gets played, lions were paid a royalty? Thoughts moved from statues to sports to fashion and more. I made crude calculations (I know no other) of the dollar potential which turned out to be significant. And with the support of colleagues, I penned a piece proposing the idea.

Money, as the saying goes, makes the world go around. And what I learnt predominantly during my human experiment period was that animals and their protectors were the poorest of the lot. For the first time I felt I might be able to help. And if the lionised pages of The Economist thought the idea worthy of discussion, maybe just maybe, I was a serviceable guinea pig after all.

My newfound optimism wasn’t to last. I ran into a colleague in the communal kitchen, and a few withering sentences as he brewed his tea cut me down to size. The idea was not original. It had been around for years. Loads of people had already done this sort of thing. Well why did they never bother to write it down? is what I never said.

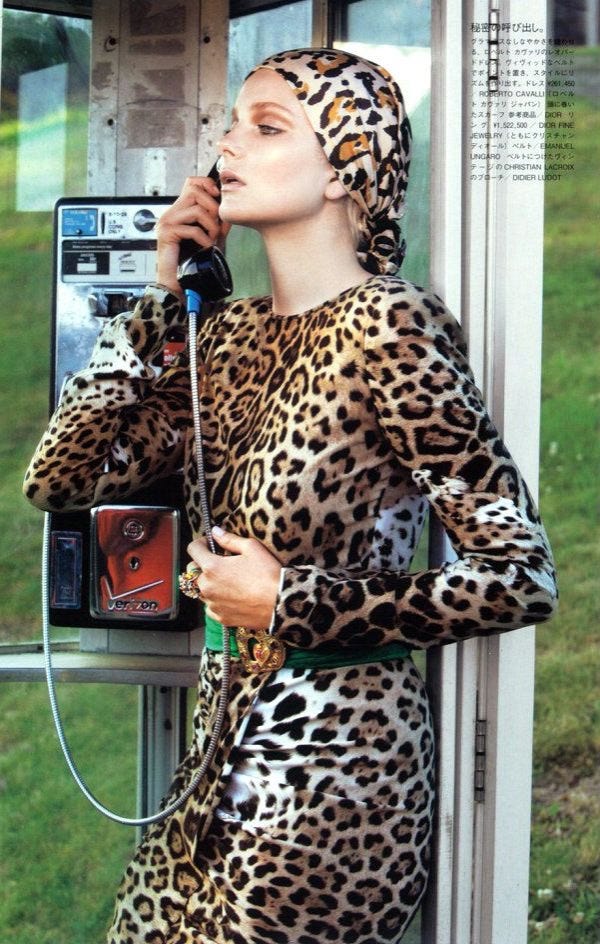

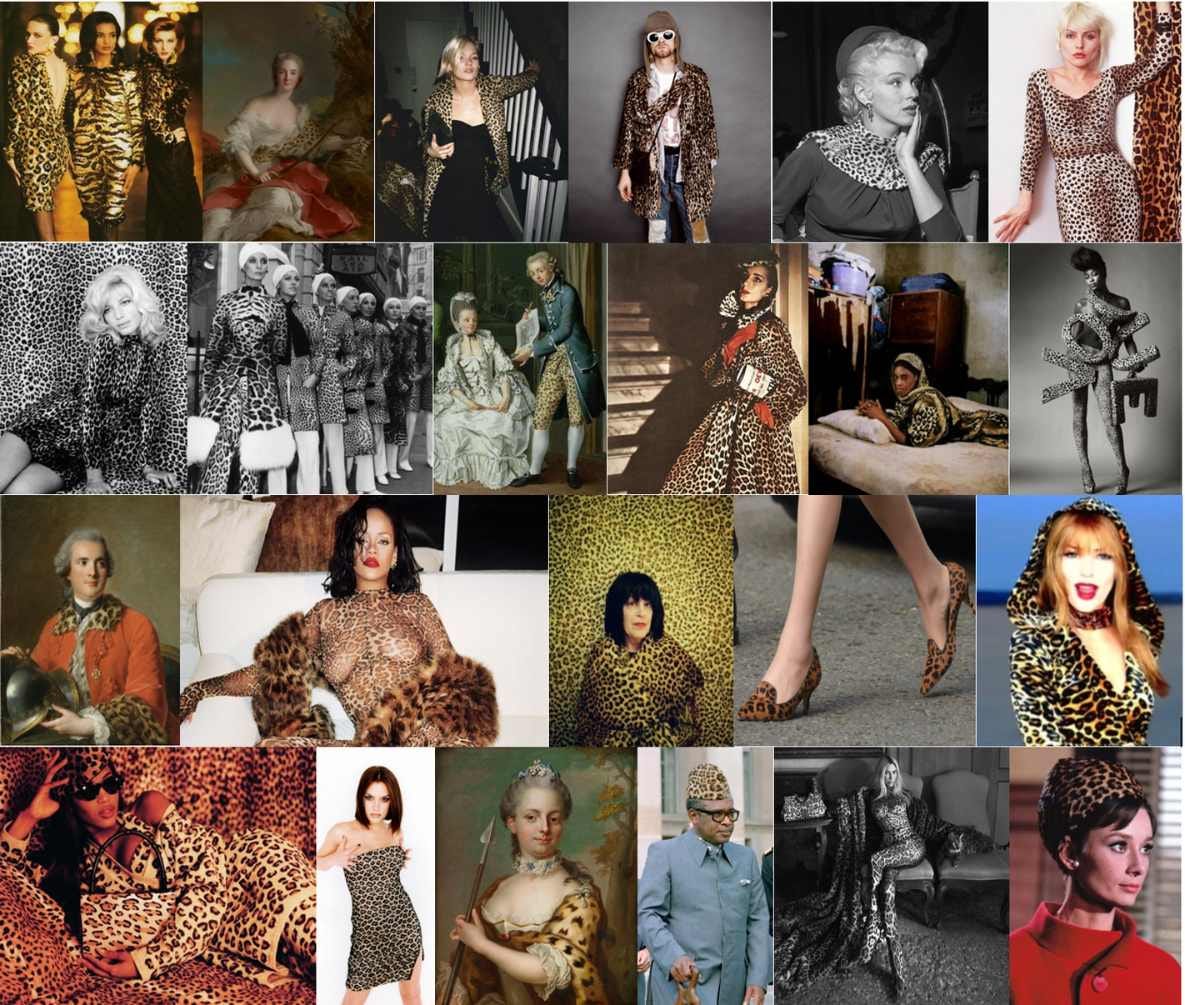

I turned to other projects. But the animal royalty idea simmered in me. And while the ubiquity of lions ran deep, it was leopard print fashion that seemed inescapably everywhere. It was like I’d bought a new car. Suddenly that make and model was all I saw. It winked at me from the squeaky covers of magazines and waved at me from Grandma’s scarf. I saw it up close in H&M and pixelated in haute couture. The opportunity seemed so big, so wasted.

Fashion also felt like the royalty idea’s closest ally. Elsewhere, this kind of ownership seemed perverse, but Christian Louboutin went to court to trademark the red sole of a shoe; Missoni got a design patent for a zig-zag; and Versace’s Medusa motif, the Vera Wang wedding dress, and Dr. Martens boot stitching, were all protected by intellectual property law. Why shouldn’t animals join the fashion patent party and collect their dues?

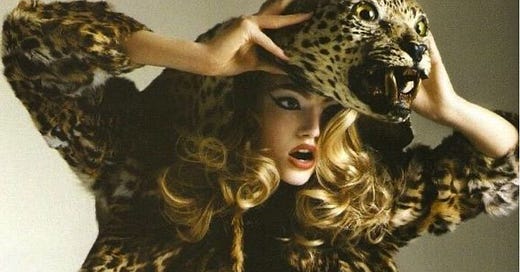

Like a sad old detective who can’t let a case go, I began making files upon files of leopard print in my spare time: Vogue covers, politicians, historical portrait paintings, grunge bands, golden age film stars… The desktop folders grew as the obsession gripped. I needed to understand. How could Cobain and Shania and Ye and Mrs Robinson all be aboard the same cruise line? How was it kink and prim and trash and chic? Was it a trend or a cult? I discovered Katie Ryder’s review of the exhibit ‘Leopard’ that captured it so well: 50 shades of sex equals a blank canvas for projection and reinvention. If cats have nine lives, then leopard print had had 9,000 and counting. It was whatever you wanted it to be.

Eight months pregnant, in the autumn of 2018, I pieced my leopard findings into another article. Summer’s viral fashion hit had been a silky leopard skirt, Net-A-Porter had doubled its buy of leopard-print pieces, and the recently wrapped runway shows were suffocating in the print as usual. The same year, the Amur leopard made headline news. Only 84 remained in the wild, landing it on the global top 10 list no-one wants to be on: most likely to be extinct. The simultaneous saturation of leopard print in fashion epitomized the complete disconnect between the world we live in and the world out there. The timing felt urgently right.

I’d gone to the source. First, finding patient zero, the original addict. Artemis was the women’s woman. Greek goddess of wildlife, womanhood, childbirth, and the moon, the inaugural femme Mother had the leopard as her spirit animal. And it was women role–playing as Artemis for portraits that had launched the first wave of leopard in western fashion in the 18th century. It was art, it was pregnant, it was spicy women with bows and arrows. It was me (preggo), it was her (spicy), it was everything (art and weaponized women).

Then second, discovering the story of Jackie O, who accidentally triggered the slaughter of 250,000 leopards after a coat she wore went viral in 1962…oops? The upshot of this catastrophic gaffe was the ensuing backlash-turned-campaigning that saw US congress ban the import of leopard fur. After that, print largely replaced pelt in Western fashion. So leopard print had already saved the leopard once before. And now, in this new, royalty–spewing reincarnation, they could do it again.

I called the piece ‘Time’s Up for the Leopard’. It was max #MeToo and peak anti–Trump. It was women marching for their pussies in the streets and on the runways. Leopard print’s history seemed to embody it all: women wearing leopard to empower themselves since the 18th century; the Artemis myth where she turns a dude into a deer for peeping without permission; and the idea we have been using the leopard’s image without consent. Wearing leopard had emboldened women and now it was our time to empower them. Looking good had never felt so good. I had never felt so good, or, dare I say it, clever. It was all there and I was so ready, laden with my puns, and myth, and metaphors.

Shelve it, said the folks in charge. There is an order of things, and you and now are not it. Besides, the leopard print trend never goes away so there’ll be plenty other ‘moments’. They had me there. I couldn’t fight my own ubiquity argument. Or my body, as our first daughter, Electra, landed. But wasn’t the world on fire? What about the leopards? The piece was never published. It was also not as clever as my memory wants it to be.

Then, early in my maternity leave, the polite but loaded ‘how was it going?’ dropped. I decided if I were to dive back in, it was going to be doing this. But I needed a different tact. These were lauded scientists. These were serious people. To persuade them I needed quantitative data not mythical allusion and fashion history and pregnancy gaffs. I needed to reinvent as serious.

I started by plugging it into Google Trends (Yes, I’m that basic). Its 12 year data history reassured me that I had not completely lost my mind. Leopard print interest had the regularity of a healthy heartrate monitor. Every autumn, without fail, it surged. I roped in my mum, a statistical math wizard. Together we learned the mysterious ‘R’ (well she did, and I ‘supervised’) and analyzed over 80,000 English language articles on leopard print. Next, I cash–bribed my sister–in–law to help quantify 10,000 Instagram posts. It was eye–bleeding stuff, but the data was building.

It would be easy to segue here into some salty feelings about pressuring myself to start work two months post birth, alone, relying on generosity of amazing women around me while trying to become a serious person to prove something. But looking out at the world, life for me has been a veritable joyride of privilege by comparison to most. Plus, if I’m honest, starting to work on this again saved me. Early motherhood is a disconcerting shitshow. Your mind and body are trashed. The new life force abruptly erases the previous you without warning. Hayley Nahmen captures the baby/life apocalypse so vividly.

It sounds daft, but thinking about leopards and leopard print brought me out of that and back to a new version of me. Obsessing over how I could convey the magnitude of its footprint both ways: the potential of leveraging something so ubiquitous in fashion and the potential of saving its real-life counterpart (because saving leopards, who are top of the food chain and have a big–ass range, comes with the bonus of saving so much other wild stuff too). It was the only time in my life that quantitative data analysis was, and will ever be, my escapism (luvuElectra).

When I’m trying to impress, I call the resulting study ‘seminal’, but that’s just a fancy word that means no one went as mad as I did over this incredibly niche thing. Since it came out, people have written nice things, and taken time to reach out to talk about it which has been unexpected and sometimes lifechanging (for better and one time, for incredibly worse). And when The New Yorker wrote about me and it, I did feel pretty vindicated about tea bag man’s neggy comments.

Of course, his words weren’t unfounded. I was annoyingly naïve and overly simplistic. And he was old guard and as confused as me about what I was doing there. But feeling misunderstood is my kryptonite. Inside I still raged a bit. I’d never claimed to be the first person to suggest raising money for wildlife through selling stuff with animals on it. If he got as far as reading just my titles, it went beyond the money. It was about the possibility of triggering a mental connection in popular culture to the animals that inspire and embody our everyday. But to get there meant coming down from the academic ivory tower, stepping outside the back–slapping echo chamber, and reaching beyond the indoctrinated tribe. It was connecting, in the simplest way, the sports lovers or fashion fanatics or Disney obsessives, basically anyone who may not give a toss about wildlife day–to–day, to the animal that inspired the mascot of their team, the print on their socks, or the protagonist on their screen. Because we all have it in us to care. Most of us actually do. It’s just hard to remember something we rarely or never see. Sometimes we need ladders, signposts, layman’s terms and a built–in collection bucket.

The problem with all the focus on quantitative data and academic think–speak is that it eradicated the aesthetics of the cultural animal phenomenon. It is, by its nature, a visual beast. Graphs and charts and numbers might make it something to some people, but it is seeing it that makes it real. You have to see hundreds of leopard print magazine covers side–by–side to begin to peek inside my mind. When I watched the eclipse, and wasn’t accidentally looking at the sun without the special specs and then going briefly blind, I was noticing cardis, coat collars, clutches in the viewing crowd. Was the print trending at the eclipse? No. My eyes now just filter it in every crowd. My own special lenses burnt onto my retinas forever. Hello madness my old friend.

So even after all this, or maybe because of all this, I still feel like I’ve let the idea down. Plus, as my obsession has unfolded, so unraveled the fashion industry itself, with news of its epic carbon footprint (#2 in global industry rankings), disastrous waste ‘programs’ (now visible from space!), and godawful human rights violations (for nice knitwear but not nice work ethics, see Loro Piana). In some ways all this has ‘helped.’ Thank you...Nasa? In recent years, when I tell people the royalty idea they get it, or at least the need for it, in a way that very few did a decade ago. But to most it also still seems decadent to tip the inspiration when fashion’s raw materials are costing the earth and no-one’s getting paid. Of course, these things aren’t mutually exclusive, but that’s another leap for another post.

These past couple of years, between another bebe (yay, Fjora!), and a transatlantic move (bye human experiment and hi New York), fixating on fashion’s forage into attempts at sustainability has done nothing to scratch my leopard itch. If anything, it’s worse. But not for any ethical or activist urgings. Oh, you’ve read me so wrong, dear reader. Staring back up from the bottom of the barrel, it’s my love of fashion winking back. It would be so much simpler if I could dismiss the whole fashion thing as silly and irrelevant from my reclaimed soapbox in my utilitarian overalls.

Own it like Grace. Kelly in the final frames of Hitchcock’s Rear Window

But it’s time to fess up and stop pretending to read Nature. I’m as frivolous and fanciful as they come. And with two little demonic daughters now in tow, the bit of the morning where we all get dressed is the fifth circle of hell: the pure joy in discovering a never before worn pair of rainbow rhinestoned leggings; the depths of despair discovering they were actually designed for a doll; the furious attempt to fit into them anyway. And that’s just me.

Beyond the morning meltdown, our madness for fashion has had me considering new sides to the leopard print puzzle. We need it just as much as we need nature. And fashion needs nature, materially and inspirationally, just as much as it needs us to want it and wear it. So how can we cheerlead the good bits – the artistry and creativity and self–expression – and at the same time save the planet that makes it all possible?

So, in not–at–all short, I’ve again got more questions than answers. And I’ve also got fewer people to answer to. This is mostly of my doing. Like many of the terminally imbibed, my addiction has turned me into a bit of a dick. The descent from bon viveur to bibulous does not happen without pissing plenty of people off.

But let me be clear, this isn’t about to teeter towards a concluding high note of faith-infused redemption. There are no lessons to learn here or encouraging crumbs for little fellow dickies. I’m still balls deep and in need of regular hits. But having regaled the root cause of my spotted problem, the genesis of this ’Stack, the reason for the pussy grabbed, this marks my next leopard metamorphosis. From now on I’ll be offloading all thoughts here.

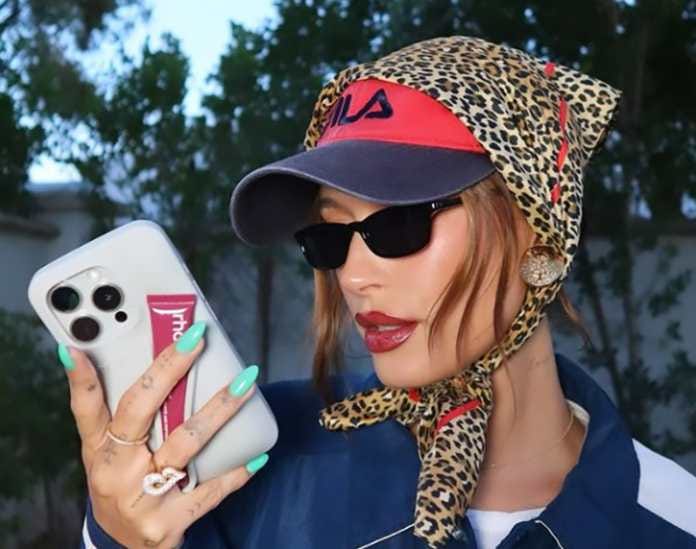

It won’t be cohesive reporting or reliable research. But if you’ve read this far then you know that. This is for the plot. It’s dolulu is the solulu stuff. A shaky step towards nowhere. Our weekly meeting. Living rent–free inside my mind these past days it’s been the Met Gala’s nature theme (next-ish post), Kate Winslet straddling a leopard for something on HBO (zero thoughts, yet), Michael Stipe in leopard print for YSL (read this and learn like I did that how he is a wonderful sartorial philosopher man), Hayley Bieber’s granny scarf (drippy drip drippin), and Roberto Cavalli who lived and died by the print of animals (more on him/this soon). So expect pointless curations of celebrity–in–leopard–print sightings, and pointed profiles on other tenuously linked things.

So grab my pussy…Substack?

I still think this is one of the best ideas ever, and it’s absurd that it has not been picked up in the way it needs to…yet.

I knew you were a good writer and that you’re hilarious but this is superb! Loved it, and love hearing the story from the beginning. Here to support you in any way I can, C!

Fashion, let alone fashion writing, kills me like I'm a lion facing an American dentist. But someone with a surname coincidentally the same as yours commanded me to suffer, and sometimes I need to pretend to be brave. So I trekked and trekked until-

WOW. THIS IS SMART AND FUNNY AND SMART. This is the original print whereas the other Markides might be a knock-off (hey, kidding!). Mythery definitely loves company.

Pleased to meet you, Caroline. I easily imagine you and your idea and work choices in a Wes Anderson movie. I'll have to subscribe to learn the story behind the spotted dick.